Japan’s Role in Global Health Governance in Absence of a Leader

Related Articles

Global cooperation in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic is at a standstill as nations prioritize domestic countermeasures. In a multipolar world, health cooperation is increasingly important in fighting the pandemic, especially as the lifting of restrictions in some parts of the world may cause further disparities. Japan must step up its role in global health governance.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) for the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on January 30, 2020. Since the International Health Regulations (IHR2005) was enacted in 2005, WHO has declared PHEIC many times including during the 2009 H1N1 (Swine flu) outbreak and the Zika epidemic in the Americas in 2016. Compared to such precedents, the length of the emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic is unusually long.

At the end of 2021, the emergence of new Omicron strains was confirmed, and in mid-February this year, the cumulative number of infected people exceeded 4 million in Japan. The virus continues to spread globally.

Unlike the Ebola and the H1N1 outbreaks which were local, COVID-19 is characterized by simultaneous multiple outbreaks around the world. As a result, each country is busy with its own response and finds itself competing for and stockpiling vaccines and treatment drugs. Partly due to the declining leadership of major powers and international organizations, there are very few coordinated steps for responses and resource allocations.

This lack of coordination is also creating disparities in the path to recovery of social and economic functions. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that he will lift all legal COVID-19 restrictions in England in mid-February. As a result of the progress of vaccination in the U.K. and the decrease in the rate of severe cases, they chose the path of living with the virus even though the infection continued to spread. France also plans to abolish the mask mandate in mid-March, and many other democratic countries are reviewing their measures and lifting restrictions.

On the contrary, there are countries that stubbornly promote zero-COVID measures. In developing countries such as Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Chad, as of early March this year, the percentage of people who have received two doses of vaccination is less than 1%. In terms of the recovery of social and economic activities, there are widening disparities globally.

Impact of Decentralization on Health Governance

Global governance in the field of health care (health governance) is a system of cooperation involving states and non-state actors to address global challenges related to people’s health using a variety of formal and informal methods. Formally, the WHO is at the helm to set global norms and adjust health disparities. International organizations and international law are basically non-binding and cannot be enforced.

Even so, historically we were able to witness some sort of collective actions based on various norms. Under such a system, the international community made great achievements such as the regional eradication of polio, the eradication of smallpox, and the spread of AIDS drugs. However, in recent years, experts have pointed to the decentralization of health governance as the result of the diversification of actors and the WHO losing its unifying force.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the above imbalance in many ways. There have been few cross-border collective efforts in the implementation of international health regulations and in the equitable distribution of resources. The IHR requires that a member country report to the WHO within 24 hours after it finds a public health emergency of international concern in its territory. But countries did not follow this provision during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, such as when Omicron first emerged, the WHO made recommendations to member states on easing of travel restrictions to prevent unnecessary disruptions to international travel and trade. However, the states rarely followed such recommendations. There are no systems to enforce the states to follow regulations and the international community must rely on each state to voluntarily comply. The pandemic has exposed the limits of such a system.

The same situation holds for resource allocation. Despite the WHO’s initiative to set up the COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access (COVAX) Facility, the first framework of its kind aimed at equitable access to resources, it was only able to deliver half the volume of vaccines as initially planned.

This was partly due to developed nations piling up on vaccines. Given the slow vaccine patent release process, experts have recommended technology transfer as a solution. In June 2021, the WHO established the mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa, but crucially, the pharmaceutical companies refused to cooperate.

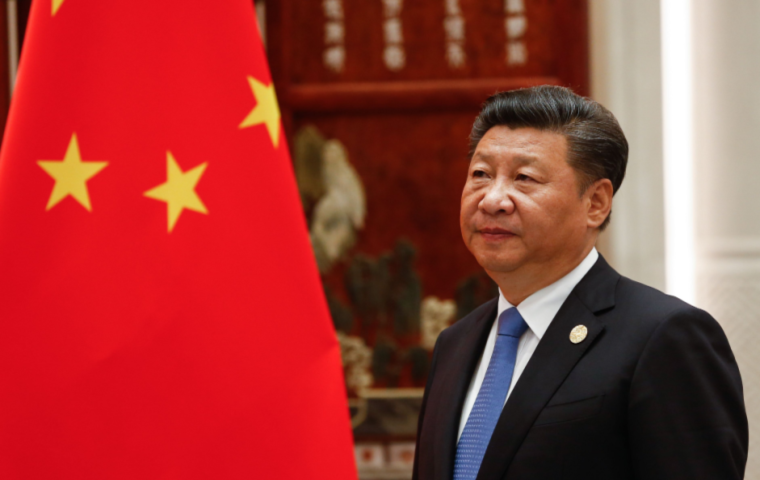

With global cooperation stalling, activities on regional and bilateral levels, and between like-minded states have accelerated. When it became clear that the WHO’s investigative team could not reveal the origin of COVID-19, independent groups and scientists from the U.S. and other states proceeded to verify the theory that the outbreak originated in the Wuhan wholesale market in China, and the theory that it leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

On the vaccine front, China and Russia, followed later by Western countries, have each developed their own diplomacy. The issue is that diplomacy on a bilateral or like-minded basis is not driven by necessity but by strategy. In fact, China’s vaccine contracts are concentrated in middle-income countries in Central and South America and some parts of Asia. In response to China’s moves, Europe and the U.S. are focused on the Asia-Pacific region. Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the lowest vaccination rate, is being left behind.

Difficulty Building a Consensus

Reaching a consensus at the global level will continue to be difficult amid the decline in international organizations and the growing conflicts between democratic and authoritarian countries. The first point of discord is the investigation of the origin of COVID-19.

In early 2021, the WHO sent a team to China, where the outbreak first occurred, but the investigation was limited to the scope permitted by the Chinese government, and the team was far from finding out the facts. The WHO set up a meeting of experts to re-investigate in the fall, but like the first time, its scope was extremely limited, and the origin remains unclear.

The second challenge is the strengthening of the IHR and the creation of a pandemic treaty. At a special session held in the fall of 2021, the World Health Assembly agreed to work on a new pandemic treaty along with revisions to the IHR.

The pandemic treaty does not replace the IHR but aims to strengthen the authority of the WHO, the responsibility of each country, and cooperation between countries regarding matters not covered by IHR such as sharing clinical trial data and ensuring a stable supply chain of medicine and medical supplies. Regular conferences among the members will help secure political commitment and enhance the effectiveness of the treaty.

The WHO still needs to determine the specific content and methods of the pandemic treaty to ensure its effectiveness. European countries have proposed provisions to ban wildlife trafficking and proposals to provide incentives for cooperation, but it is unclear whether other countries will support them.

In addition, as of the beginning of 2022, only about thirty countries, mainly in Africa and Europe, have expressed clear support for the WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. He is expected to continue to face difficulties demonstrating leadership in various areas.

Multilayered Health Governance

Systems for health cooperation have advanced more at the regional level than at the global level. Different regions face challenges from different infectious diseases, such as malaria in Africa and yellow fever in the Americas. In Asia, before the war, there was the Singapore bureau for infectious diseases information under the League of Nations Health Organization, which served as a base for regional health cooperation.

The responses to the COVID-19 pandemic made evident the fraying of cooperation at the global level, leading to movements at the regional level to review cooperation. The European Union (EU) announced the establishment of the European Health Union in the fall of 2020.

The purpose of the organization is to enhance preparedness and response within the EU by monitoring the regional supply of medicines and medical devices, coordinating information and research on vaccine clinical trials, vaccine efficacy and safety, developing surveillance systems, and monitoring hospital bed occupancy rates and the number of healthcare personnel.

In Latin America, the WHO America Regional Office announced the establishment of a platform to promote regional manufacturing of the COVID-19 vaccine in September 2021. In Africa, a regional framework to procure medicines and medical supplies within the continent was established, allowing for partnerships between regional organizations such as the African Union (AU), Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, to play a major role in the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines from outside the region.

Partnerships by like-minded countries are also becoming more active. The QUAD, a framework of diplomatic and security policies of the four countries of Japan, the U.S., Australia, and India, has been assisting Indo-Pacific countries with vaccination programs through cold-chain support and by building manufacturing capacity since the spring of 2009.

The Role of the Global Cooperation Framework

The major principles of multilateral cooperation and the rule of law, which are the foundation of the post-war international order, are now facing a major crisis. The fact that Russia, a permanent member of the Security Council, exercised its veto power in adopting a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the UN Security Council clearly demonstrated the inflexibility and limitations of international organizations.

At the same time at its emergency special session in early March, the UN General Assembly adopted by majority a resolution condemning the Russian aggression in the strongest terms. Although the resolution has no binding force, it confirmed the solidarity of the international community and provided a basis for nations to resolutely oppose Russia’s violation of territorial integrity. International institutions are increasingly showing their limitations, but they still play a marginal role in providing a forum for relevant actors, setting out norms and rules, and eliciting and sustaining political engagement.

The same can be said about health cooperation. It is easy to lament the lack of global cooperation and WHO’s leadership, but these are already factored into the inherently anarchic nature of the international community. To improve the situation in line with the changes in the global environment, we need to think about what to change and supplement with new equipment and other means within the existing framework.

As the world becomes increasingly multipolar, it will be more difficult for international organizations to garner international cooperation. Even under such circumstances, the WHO’s fundamental role of setting various norms on health and eliciting and fostering political commitment to maintain those norms will not change.

Regarding the new pandemic treaty, considering the effects of infectious diseases on climate change, trade, and other matters, it should include comprehensive provisions that go beyond public health. It should also establish a mechanism to provide incentives for members to cooperate. It should regularly hold conventions to review implementations, which can serve as a mechanism for involving member states. If the treaty can do the above, it should be deemed a success.

However, this alone is not enough to prepare for the next pandemic. There should also be efforts on multiple channels such as on state and regional levels, and among like-minded countries, and in public-private partnerships, to conduct surveillance, develop medicine and build manufacturing capabilities of the medicine, and arrange prior agreements of emergency travel restrictions.

Japan Should Proactively Build a System of Cooperation

Japan should seek to strengthen cooperation with its neighboring countries. In Asia, unlike Europe and Africa, there is no system of regional health cooperation that covers the entire region. There is only piecemeal cooperation between allies. The Japanese government launched the ASEAN Centre for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases in 2020, which Japan could work around to develop regional cooperation.

Japan, China, and Korea have been holding trilateral health ministers’ meetings since 2007. At the end of 2021, the ministers released a joint statement advocating the strengthening of pandemic preparedness and information sharing. The countries also adopted a joint action plan, which included provisions such as the promotion of human resource development. It remains to be seen whether these plans will materialize, given the ongoing diplomatic tensions between these countries.

Nonetheless, as previously noted, establishing a flexible mechanism with neighboring countries will be beneficial to the preparedness and response of all states involved. There are regular research exchanges between Japan’s National Institute of Infectious Diseases, China’s CDC, and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

There is also a movement to explore vaccine cooperation under a framework that includes South Korea in addition to the QUAD. From a long-term perspective, there is some value in aiming for a more comprehensive framework for cooperation in Asia, whether it be formal or informal.

Japan needs to be active on the global level as well. In February of this year, the WHO established a hub in South Korea to conduct training in the development and manufacturing of vaccines and therapeutic drugs for middle and low-income countries. In the fall of 2009, the WHO opened a hub in Germany as a base for cooperation in infectious disease detection and information-sharing.

France has operated a WHO office in Lyon since 2001 to provide support for capacity building for health emergencies and preparedness in developing countries. Japan has been involved in efforts to achieve universal health coverage. It should continue to focus on this while contributing to capacity building in other countries with a medium to long-term perspective.

Regarding the proposed pandemic treaty, Japan should play a role in devising a concrete and effective draft as well as coordinating views among states. Tough times are ahead for health governance amid a volatile world, but the threat of the next pandemic looms large.

It is essential for us to prepare for the next health emergency through multilayered health governance, by understanding and balancing the nature of cooperation at each level.

This article is a translation of the Japanese original published in the March/April 2022 issue of Gaiko (Diplomacy) magazine.

Kayo Takuma is a professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo. She worked as a research associate at the Department of Pan Asian Studies at the University of Tokyo and assistant professor at the Faculty of Foreign Languages at Kansai Gaidai University. She is the author of Kokusai seijino no nakano kokusai hoken jigyo [Healthcare services in international politics], Jinrui to yamai [Humankind and illnesses] among others.